Brandan Montclare, Natacha Bustos and Tamra Bonvillain’s ‘Girl-Moon’ story arc comes to its conclusion in this week’s twenty-second Moon G and Devil D. It’s a rather quick wrapping up of the adventure that is a bit heavy on exposition, but is a lot of fun nonetheless; with some very neat metaphors and absolutely beautiful art.

After a short jaunt to another dimension where Lunnela and DD landed on a counter-earth and met different versions of themselves, Moon Girl has managed to pilot the Moon Mobile back to Illa The Living Moon. Illa is both relived and angered to see the pair return. The living moon has spent much of her existence in isolation and has come to expect abandonment from others. She was furious that Moon Girl had left in the first place and now angrily suspects she will once more be rejected and left on her own.

Illa is able to control every molecule comprising her satellite form, which allows her to take on a more anthropomorphic shape… though these human-like shapes tend to mirror her ambivalent feelings of need and fear. It makes for a rather neat visual trick of showing Illa as having one body but two heads, highlighting her mixed feelings. Lunella literally has to push the two bodies together in order to get Illa to thinking clearly. The unifying principle being that she does not want to be alone.

Lunella is finally able to get Illa to trust her and follow her to a place on the moon;’s surface suitable for Lunella’s plan. Ill accompanies Lunella by manifesting her own dinosaur to ride on, this one a stegosaurus made up of the rocks and soil of her cosmic body. It’s super cute.

Reaching a high point on the moon, Lunella sets up a contraption that utilizes the Omniwave Projector in order to project a holographic version of her and Devil D beyond the dark side of the moon and to the front of the host planet. And there she comes face to ‘face’ with Illa’s father, Ego The Living Planet.

For those of you who only know Ego from the movie, Guardians of The Galaxy Vol. 2, Ego is not actually a Celestial. Rather he is a randomly occurring space anomaly wherein a planet gained sentience. He first appeared int he pages of The Mighty Thor (#132) during a time in which Stan Lee and Jack Kirby were really stretching the bounds of cosmic storytelling. It was also one of the first instances where Kirby began to incorporate elements of collage into his illustration and Ego’s first appearance remains one of the most striking images from Kirby and Lee’s golden age of innovating the comic book medium.

Anyways, Ego is as boastful and proud as his name implies. He finds Lunella’s appearance in front of his as an intrusion and demands she go away. Lunella uses Ego’s cantankerousness to her advantage. She goads at Ego until he tries to destroy her; which leads him to realize she is merely a holographic projection emanating from elsewhere. Further angered, Ego uses his powers over gravity and whatnot to track the source of the transmission and bring it in front of him. And this causes him to essentially grab his moon/daughter and turn its circumference around.

The reason Illa could never see her father and her father could never see her is that their orbits were fixed so that Illa’s face was on the part of the moon turned away from its host planet… her back was constantly turned to her father. Ego’s actions in trying to catch Lunella caused a realignment of the orbit, thus allowing Ego and Illa to finally face one another. And with we get to see the happy reunion between father and daughter. Ill will be alone and isolated no more.

Their mission accomplished, Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur head back to their Moon Mobile so to return to earth.

Inter-spliced throughout the narrative is a subplot involving the android duplicates that Luella had created so that her trip to the cosmos might go unnoticed by her parents, teachers and fellow classmates. One of these android duplicates, Lunella Bot Seven, has gained a degree of sentience of her own. Having befriended the disconnected head of a DoomBot that Lunella has ill-advisedly kept in her laboratory, Lunella-Bot 7 has endeavored into something of an existential crisis and search for meaning. How this will resolve is yet to be seen. In the meantime, the android’s gaining sentience and her actions has caused an even further alienation between Lunella and her parents.

The parallels between Illa’s desperate desire for connectivity and dependency on her parent and Lunella’s own disconnect and independency from her own parents makes for a very interesting juxtaposition. Lunella’s taking her mom and dad for granted, her emotional disconnection from them and how this has effected the family as a whole has been a plot point in the series that has percolated from the very start. And I’m hoping that the actions of Lunella-Bot Seven will finally cause the matter to be more fully addressed int he narrative.

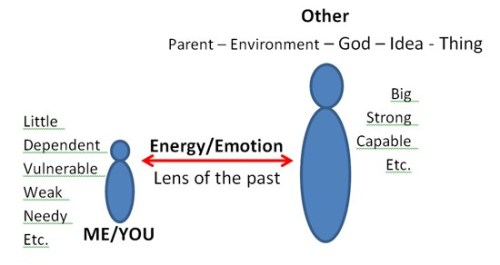

Like many extremely smart people, Lunella is much better at doling out advice and fixing other people’s problems than she is at taking on her own issues. There’s a panel in today’s issue where Lunella is trying to explain to Illa the reasons why she and her father cannot see each other (due to the two astral bodies being in a fixed orbit). It’s plot exposition, yet is also quite evocative of the psychological construct of object relations.

Object relations is a rather old, but still quite pertinent theory from developmental psychology. The theory holds that through good parenting, the child comes to formulate an internalized object or psychic image of the parental figure. Having internalized a psychic presence of the parent within the self imbues the growing child with confidence and the ability to handle things on their own. It facilitates independence by way allowing the child to feel that their parent is always with them on an emotional level even if they are separated on a physical level.

For example, a young child can go off to the first day of school and not be terrified over the prospect of being join their own and separated from their parent because a part of the parent has been taken in as an internalized object. The child is not fully alone because they have the internal object to accompany them and offer support, guidance and containment.

Of course the process in which a child cultivates internalized objects is not seamless nor instantaneous. It occurs gradually over time, with fits and starts, steps forward and steps backward. The lack of good object relations tends to lead to significant difficulties with anxiety, as well as temper tantrums and splitting (seeing things as either all good or all bad). We see each of these symptoms in Illa (with the splitting being depicted in a rather literal sense). Illa’s father is actually right behind her, he has always been there; yet Illa cannot feel his presence because they were separated too soon. There was not time for Illa to form an internalized object of her father and is thus overwhelmed by loneliness and anxiety. Eventually, Illa should be able to function on her own, perhaps even leave her father’s orbit and venture out into the larger universe. Yet she will need time to truly bond with her dad in order to formulate an internalized version of him, a psychic object that will provide confidence and security even when she is on her own.

A matter that is all too often overlooked in this whole theoretical construct is that good object relations go both ways. To the same extent that the child needs to form a guiding internal object of the parent so to gain self confidence and independence, so too does the parent need to form an internal object of their child to deal with their own pains of separation and worry.

We see this with Lunella’s mom and dad who are both kind of falling apart because their daughter has individuated from them before either of them were ready for it. Lunella points out to Illa the one constant in the ever expanding universe: ‘we’re all moving apart from each other. It’s actually light-years but only feels like little bits.’

This is true in astrophysics and is also true in parent/child relations. From the moment a child is born, they begin the slow and inevitable process of moving away from the parent, individuating and becoming separate. The distance apart will eventually become akin to light-years, but it needs to seem just as little bits so to prepare both parties for the separation; to give time for internal objects to be formed.

Mr. and Mrs. Lafayette have been denied this time. Their daughter is just too precocious, too quick to separate a try to sate her curiosity over the grander universe around her. As a result, they do not have a healthy internal object of their daughter. They have a false, unsatisfying object in the form of the robot duplicate Lunella has left behind.

As a consequence, Lunella’s parents are in as much pain and distress as Illa was. And it makes for a cruel irony that Lunella would venture off into the distant cosmos to assist Illa and solve her suffering while her own parents are left behind with their own suffering unaddressed. One would think that the smartest person on the planet would be aware of something so obvious…

Once again, for all of her incredible intellect, Lunella still lacks wisdom. Extra-dimensional astrophysics is child’s play to her, yet the simple matter of interpersonal relations remains a source of ignorance and bafflement.

The next issue is a Legacy tie-in and looks to see Moon Girl meeting the original Moon Boy. While Moon Girl is all brains, Moon Boy was all heart and hopefully the two meeting one another might teach Lunella something; and that the whole ordeal with Lunella-Bot Seven will facilitate a much needed reckoning between Lunella and her mom and dad. We’ll see…

Similar to the issue where Moon Girl met Dr. Strange, the art team of Bustos and Bonvillain do not waste the opportunity to stretch their creative muscles. Much of Moon Girl’s adventures have taken place in urban environments and the art has done an excellent job of illustrating the cityscape of the Lower West Side and whatnot. With this story, however, Bustos and Bonvillain get to depict a more cosmic and far out atmosphere and it’s a terrific fit. Bustos’ confident line and animated style, coupled with Bonvillain’s ultra-vibrant color pallet really makes the cosmic setting come to life, popping off the page with Kirby-style crackle. As the series progresses, I hope that writer Brendan Montclare will tell more stories that enable the art to further showcase Bustos and Bonvillain’s great knack for depicting cool and new environments.

Once again, highly recommended. Although the resolution of the story relies a bit too heavy on exposition, it was a satisfying conclusion nonetheless; with art that continues to get better and better with each new installment.

Three and a half out of five Lockjaws!

Inhuman Solicitations for July 2017

Inhuman Solicitations for July 2017 Moon Girl & Devil Dinosaur #21 Review (spoilers)

Moon Girl & Devil Dinosaur #21 Review (spoilers) Ms. Marvel #17 Review (spoilers)

Ms. Marvel #17 Review (spoilers) Inhumans Trailer – Dissection and Review

Inhumans Trailer – Dissection and Review Episode 78 – Agents of SHIELD Review Season 7 Episode 8 “After, Before”

Episode 78 – Agents of SHIELD Review Season 7 Episode 8 “After, Before”